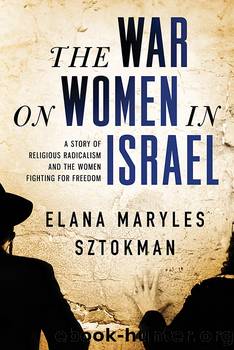

The War on Women in Israel by Elana Maryles Sztokman

Author:Elana Maryles Sztokman

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Sourcebooks

Published: 2014-05-15T00:00:00+00:00

Chapter 7

A NOT-SO-PERFECT UNION: MARRIAGE, DIVORCE, AND THE ENDLESS SUFFERING OF CHAINED WOMEN

Languages reveal a lot about the culture to which they belong. Some of the most informative parts of the language and the culture(s) in which it is spoken are often the hardest to translate. For example, the fact that there are fifty-three different words for types of snow in Inuit tells us how important snow is in Inuit culture.1 The common Thai word has no single-word equivalent in most other languages, but it means âsincere kindness and willingness to help others, even before they asked, without expecting something in return.â Itâs the same for the Swedish mÃ¥ngata, âa roadlike reflection of the moon in the water,â or the Greek âfriend-honor,â âto respect and honor your friends, the quintessence of Greeks.â2 These words are like linguistic secrets: they reflect unique elements of their culture that no other culture can quite emulate, at least not in a word.

Hebrew, too, has a word that is untranslatable. When I first learned this, I was excited at the prospect that my beloved language also has something specialâuntil I discovered that the untranslatable word is not a source of honor or pride but rather a source of shame. The untranslatable Hebrew word is agunah, which most literally means a âchained woman.â An agunah is a woman who is stuck in a marriage that she has already exited because her husband refuses to grant her a divorce, something notoriously unique to Jewish life. There doesnât seem to be a one-word linguistic equivalent to this in other languages or societies, and that, in and of itself, is telling of the values of Jewish culture.

The problem of the agunah in Jewish culture has existed for two millennia. It is based on the original Torah, which states that divorce happens when a man gives his wife a writ of divorceâknown as a gettâand thus releases her. Rabbis over the generations have interpreted this to mean that only a man can âgiveâ a gett or, effectively, initiate a divorce. (Although, interestingly, historical evidence suggests that this was not always the case. Documents from the Cairo Geniza show that in fifth century BCE Elephantine, women could initiate divorce and give their husbands the gett.3) Starting in the Mishnaic and Talmudic periods from the second century forward, when the oral rabbinic law was codified, the standard law became fixed that divorce takes place through the actions of the man onto the womanâeven against her willâand not in reverse. As the Babylonian Talmud clearly states, âA woman is sent away [by her husband] whether she wants to be sent away or even if she doesnât want to be sent away, a man sends away his wife only if he wants to.â4 Today, Jewish women are fully dependent on the will and volition of their husbands in order to exit marriage.

âRachel,â a forty-eight-year old mother of five living in an Orthodox neighborhood of Jerusalem and a long-time colleague and friend of mine, faced this exact conundrum.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(16685)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(11499)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(7815)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(5809)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5062)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(4841)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(4798)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(4463)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(4449)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(4434)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(4428)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(4357)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4095)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4046)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4029)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(3900)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(3884)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(3794)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(3743)